2010年5月3日 星期一

¡Jesús de Machaca!

-Mirando un video educativo sobre animales-

¨¿Cuál es el animal más grande en el mundo?¨ preguntó Profe Roly. ¨La ballena o el elefante?¨

¨¡El mono!¨ gritó una pequeña estudiante.

¨La ballena, es,¨ dijo el profe entre risas ingenuas de los demás. ¨Y dónde viven las ballenas?¨

¨¡En el agua!¨ dijeron todos.

¨Si, son las criaturas más grandes en el agua. Y qué es el animal más grande de la tierra?¨

¨¡El mono!¨ gritó la misma chica que antes.

¨El elefante, es¨ sonrió el profe entre otra onda de risas. ¨Y dónde viven los elefantes?¨

¨En Los Yungas!¨ (una región trópica en Bolivia donde definitivamente no existen elefantes, ni siquiera en zoológicos.

Así pasan las clases en Jesús de Machaca, un pueblito indígena ubicada en el altiplano por la frontera entre Bolivia y Perú. Los habitantes son aymaras, la raza del actual presidente boliviano Evo Morales. Es un lugar bien aislado, con apenas 600 de personas bajo la jurisdicción de la alcaldía. El estilo de vida aquí encarna lo típico del campesino boliviano, caracterizado por la falta de internet, suministro consistente de agua y electricidad, movilidades de transporte, así como una dieta que normalmente sólo consiste en papas, papas, y más papas. Además, bastantes estudiantes tienen que trasladar hasta dos horas de distancia a pie para llegar a la escuela más cercana.

Para los de ustedes que no sepan mucho sobre el sistema educativo de Bolivia, los alumnos solamente van a la escuela cuatro horas por día. Eso significa que para algunos campesinos, hay que pasar tanto tiempo andando a sus clases que aprendiendo en ellas. No me sorprende que muchos padres simplemente opten por utilizar a sus hijos para la ganadería o agricultura en vez de enviarles a la escuela. La educación boliviana nunca ha sido conocida por su calidad, especialmente en el campo. Una vez enseñé a una clase que no pudieron entender ¨My name is Clarke, what is your name?¨ luego de seis años de enseñanza de inglés…

Gracias a mi amiga polaca Alexandra, tuve la increíble oportunidad de empezar a trabajar aquí en este pueblo ayer. Hace dos meses y media que trabajo como voluntario en La Paz y El Alto, y aunque he trabajado en proyectos con muy buenas personas, éstos de la ciudad sencillamente no me colmaron mis aspiraciones. Sólo me mandaban a hacer trabajos prebendas que podían ser hechos por quienquiera tenga el tiempo, y me sentía que yo estaba desperdiciando mi tiempo cuando podría contribuir mucho más con mi talento. Decidí a emprender mi año sabático porque quería aumentar mi conocimiento de nuestro mundo y forjar una cosmovisión más madura y completa a través de trabajos de voluntariado en lugares que verdaderamente necesitaran ayuda… y no necesité mucho tiempo para darme cuenta que La Paz no era uno de estos lugares. Ya estaba llena de voluntarios extranjeros — y si bien ellos estaban haciendo buenas cosas con niños de las calles, La Paz realmente no tiene tantos sin techo para una ciudad de su tamaño. Después de casi tres meses de trabajar en La Paz, ya no pude aguantar el sentido de inutilidad. La verdad fue que no estuve haciendo nada para positivamente redundar la situación social. Todo lo que estaba haciendo fue volverme un flojo hijo de puta sin ninguna motivación. En resumen, no estaba aprovechando mi maravillosa oportunidad de experimentar y mejorar nuestro mundo durante mi año sabático. Esta situación tuvo que cambiar.

Así que un día de repente apareció una idea en mi mente: ¨¿Por qué no me pongo a trabajar con Alexandra en su proyecto en Jesús de Machaca? Me acuerdo que Alex me dijo que nuevos voluntarios son bienvenidos.¨ No tuve que pensar mucho—instantáneamente supe que fue la solución que me salvaría de mi falta de inspiración. No sé cómo lo supe, sólo recuerdo que me sentí la misma certidumbre que tuve cuando la genial idea de postergar mi ingreso a la universidad entró mi mente. Decidí a seguir mi intuición por ese entonces, y como resultado he experimentado los mejores momentos de mi vida a lo largo de mis fascinantes viajes. Pues obviamente hubo que seguir esta intuición otra vez :)

Sólo he trabajado en Jesús de Machaca por 2 días, así que aún es demasiado temprano para sacar conclusiones sobre mi cambio del entorno trabajador. Pero lo que está seguro es que tendré una experiencia verdaderamente ¨boliviana¨ durante mi tiempo acá en Jesús de Machaca, viendo videos de elefantes y ballenas con niños aymaras que sólo conocen un mundo de llamas, vacas, y ovejas.. :)

English Version

"What's the biggest animal in the world?" asked Mr. Roly. "The whale or the elephant?"

"The monkey!" shouted a little indigenous student.

"It's the whale," smiled Mr. Roly amidst the ingenuous laughter of her classmates. "And where do whales live?"

"In the water!" cried the entire class.

"Correct. Whales are the biggest creatures in the water. So what's the biggest animal on land?"

"The monkey!" shouted the same little girl.

"It's the elephant," smiled Mr. Roly between another wave of laughter from the class. "And where do elephants live?"

"In the Yungas!" (a region in Bolivia where elephants definitely don't exist—not even en zoos.

This is what classes are like in "Jesús de Machaca," a small town located in the plateaus near the border between Bolivia and Peru. The villagers here are "aymara," the same race as the current Bolivian president Evo Morales. It's a pretty isolated town, with hardly 600 inhabitants under the rule of the local authorities. The daily routines here embody the typical lifestyle of the Bolivian country-dweller, characterized by the lack of internet, transportation, supply of water and electricity, and variety of diet (normally consisting of nothing but potatoes, potatoes, and more potatoes). In addition, many students must make a daily trek of two hours in order to arrive at their closest schools.

For those of you who don't know much about the Bolivian education system, the students down here only go to school for four hours per day. This means that many of them spend as much time getting to their classes as learning in them. It doesn't surprise me that many parents simply choose to utilize their children as additional hands in farming and cattle raising instead of sending them to school. The Bolivian education system has never been known for its quality, especially in the countryside. I once taught an English class that couldn't understand "My name is Clarke, what is your name?" after six full years of previous English classes…

Thanks to my great Polish friend Alexandra, I had the amazing opportunity to start working in this tiny village yesterday. I'd been volunteering for two and a half months as in La Paz (the capital of Bolivia) and El Alto (the capital's neighboring city of chaos), and although I'd been working In projects with great people, these projects simply weren't fulfilling my aspirations. The project coordinators only gave me trivial work that could be completed by anybody who cared to take the time and do it, making me feel like I was completely wasting my time while I could be contributing so much more with my talents. I decided to embark on my gap year because I wanted to widen my knowledge of our vast world and forge a more complete worldview through volunteering in places that desperately needed help… and I didn't need much time to reach the conclusion that La Paz wasn't one of those places. The city was already full of foreign volunteers, and while some of them were certainly doing great work with street children, La Paz really didn't harbor that many homeless people — especially for a city its size. After nearly three months of working in La Paz, I just couldn't stand the feeling of uselessness within me. The simple truth was that I wasn't doing anything to make a positive impact on the societal situation. All that I was doing was losing motivation and becoming a lazy bastard. In short, I wasn't taking advantage of my amazing gap year opportunity to experience and help out our vast world. This situation simply had to change.

So one day an idea suddenly appeared in my head: "Why don't I start working with Alexandra in her project in Jesús de Machaca? I remember hearing that new volunteers were always welcome." I didn't need to think about it much — immediately I knew that it was the solution that would save me from my utter lack of inspiration. I don't know how I knew; I just remember that I felt the same certainty as I did when the brilliant idea of deferring my college entrance entered my head. I decided to follow my intuition back then, and as a result I've experienced some of the best moments of my life throughout my fascinating travels. Obviously, I had to follow this same intuitive feeling one more time :)

I've only worked in Jesús de Machaca for two days, so it's still too early to reach conclusions about my change of working environment. However, what's certain is that I'll definitely get the chance to live a truly "Bolivian" experience during my stay here in this tiny village, watching videos about whales and elephants alongside little indigenous kids who've only seen a world with llamas, cows, and sheep.. :)

2010年3月9日 星期二

Un Retrato de la Coyuntura Indígena Boliviana a lo Largo de Su Historia / An Overview of the Indigenous Situation Throughout Bolivia´s History

No he escrito un blog por mucho tiempo.. ¡casi 1 mes! Es que ya he empezado a trabajar, y he estado muy ocupado. Por otro lado, debo admitir que también he estado muy perezoso, sin tener las ganas de escribir algo. Sin embargo, he leído mucho, terminando dos libros:

2) Un libro de texto para los estudiantes secundarios acerca de la historia y geografía de Bolivia. Lo que me impresionó sobre esto libro fue que no sólo abordó los dos dichos temas, sino también incluyó capítulos en torno al medio ambiente, desarrollo sostenible, y responsabilidad social en el proceso democrático. Nunca he leído un libro de texto tan completo que abordó tantos temas prácticos a parte de las académicas.

Ahora me alegra decir que tengo un conocimiento mucho más completo del país en que estoy viviendo. Además, después de obtener un retrato general de los acontecimientos a lo largo de la historia boliviana, me estoy poniendo a darse cuenta de la verdadera significancia del arribo al poder del Presidente Evo Morales, el primer mandatorio indígena de Bolivia elegido mediante comicios electorales democráticos.

De todos modos, hablemos de la cuestión central: ¿Qué habría ocasionado tanto demoro en la adquisición de poder por una raza en la mayoría? En otros países del mundo, existía una discriminación contra razas de la minoría, tal como el racismo ejercido contra negros en el Occidental. Pero en estos casos los blancos contaban con su ventaja de números para mantener su dominancia sobre las otras razas; en Bolivia, por otro lado, aunque los mestizos (los que tienen sangre mezclada entre blanco y originario) y criollos (blancos o mestizos nacidos en Latinoamérica) nunca habían tenido más de 40% de la población, lograban mantener un entorno de supresión contra los originarios mayorías del país. Aun hasta los fines del siglo XX, cuando se introdujo leyes para promover la participación popular en la democracia, los élites seguían manteniendo un ambiente político caracterizado por la exclusión y el avasallamiento del estrato bajo de la sociedad. Debido a la falta de conocimiento sobre el proceso electoral, los indígenas no habían ejercido su influencia a la urna hasta la llegada de Evo Morales y su partido Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) a la escena nacional.

La historia de discriminación tiene raíces desde hace mucho tiempo, empezando, por supuesto, con la invasión de conquistadores españoles en los siglos XV y XVI. Ya deberíamos haber aprendido sobre las atrocidades cometidos por estos sinvergüenzas para ahora, así que omitamos esta época y sigamos con la coyuntura indígena en los principios de la república independiente. Los indígenas, liderada por jefes destacados tal como Túpac Katari, encabezaron las primeras esfuerzas para liberar el país de los españoles, ocasionando una serie de sublevaciones y levantamientos que eventualmente agotaron la autoridad española y logrando la independencia. Sin embargo, pese al papel imprescindible desempeñado por los indígenas durante el proceso hacia la independencia, ellos no fueron invitados cuando se estuvo formando la nueva constitución del país. Así los élites (blancos, mestizos, y criollos) fundaron una república que estableció una diferencia discriminatoria entre bolivianos y ciudadanos. Sólo lo último podía gozar del derecho al sufragio, y sólo se podía ser incluido en este grupo privilegiado si sabías leer y escribir, así como poseer ciertos recursos económicos.

La historia de discriminación tiene raíces desde hace mucho tiempo, empezando, por supuesto, con la invasión de conquistadores españoles en los siglos XV y XVI. Ya deberíamos haber aprendido sobre las atrocidades cometidos por estos sinvergüenzas para ahora, así que omitamos esta época y sigamos con la coyuntura indígena en los principios de la república independiente. Los indígenas, liderada por jefes destacados tal como Túpac Katari, encabezaron las primeras esfuerzas para liberar el país de los españoles, ocasionando una serie de sublevaciones y levantamientos que eventualmente agotaron la autoridad española y logrando la independencia. Sin embargo, pese al papel imprescindible desempeñado por los indígenas durante el proceso hacia la independencia, ellos no fueron invitados cuando se estuvo formando la nueva constitución del país. Así los élites (blancos, mestizos, y criollos) fundaron una república que estableció una diferencia discriminatoria entre bolivianos y ciudadanos. Sólo lo último podía gozar del derecho al sufragio, y sólo se podía ser incluido en este grupo privilegiado si sabías leer y escribir, así como poseer ciertos recursos económicos. Faltando una voz en la política de su nación, la población indígena se hallaba continuamente siendo las víctimas de políticas mal diseñadas. El librecambio propugnado por muchos mandatorios, por ejemplo, creó una apertura de bienes manufacturados por países industrializados que diezmó muchas fuentes de la economía local, tal como la de los textiles. Las formas tradicionales de artesanía simplemente no pudieron competir con los precios bajos de productos de fuentes industrializadas sin el apoyo de aranceles proteccionistas.

Otro caso en que los indígenas tuvieron que soportar políticas injustas fue cuando Melgarejo — sí, el primer mandatorio indígena de Bolivia — remató el sistema de propiedad comunal, algo central a la identidad y bienestar indígena. Así se desconoció la propiedad de tierras comunitarias, allanando el paseo para hacendados ampliar sus dominios por adquirir las tierras perdidas por los indígenas. Como resultado, los dueños legítimos de la tierra se convirtieron en trabajadores de mínimo sueldo en haciendas bajo condiciones cerca de la esclavitud. Así los originarios fueron tratados a lo largo de la historia boliviana.

Otro caso en que los indígenas tuvieron que soportar políticas injustas fue cuando Melgarejo — sí, el primer mandatorio indígena de Bolivia — remató el sistema de propiedad comunal, algo central a la identidad y bienestar indígena. Así se desconoció la propiedad de tierras comunitarias, allanando el paseo para hacendados ampliar sus dominios por adquirir las tierras perdidas por los indígenas. Como resultado, los dueños legítimos de la tierra se convirtieron en trabajadores de mínimo sueldo en haciendas bajo condiciones cerca de la esclavitud. Así los originarios fueron tratados a lo largo de la historia boliviana. Paradójicamente, mientras reprimiendo los indígenas, el estado boliviano simultáneo contaba con las aportaciones tributarias de los mismos para sostener el funcionamiento del país. Entre 1827 y 1867, los originarios aportaban un promedio de casi 40% de los impuestos estatales, a pesar de que no tuvieron una forma económica formal de intercambio. Era una situación de muchas obligaciones y pocos derechos para este sector de la población.

En este contexto de la continua supresión de la población originaria, el triunfo de Evo Morales tiene aun más significancia. Si bien a partir de los medianos del siglo XX los indígenas lograban organizarse y conseguir importantes reconocimientos de sus derechos y tradicionales, no llegaron a ser una fuerza en la escena política nacional hasta la llegada de Evo Morales. ¿Quién es esta leyendaria figura que finalmente empujó el movimiento originario boliviano más allá del ¨Tipping Point¨ de no regreso?

Hablaremos de este tema la próxima vez. Ya me voy a agotar traduciendo todo lo que he escrito. ¿Por qué siempre escribo tanto?

English Version

1) Jefazo: Retrato Íntimo de Evo Morales. Written by an Argentinean who followed the Bolivian President Evo Morales wherever he went for a couple of years. Extremely well written, with the most specific details that help the reader form a complete illustration about this incredible leader.

2) A middle school textbook about the history and geography of Bolivia. What really impressed me about this book was that it didn’t only cover the two subjects of history and geography, but also included chapters about the environment, sustainable development, and social responsibility in the democratic process. I’ve never read a textbook so complete that covered so many practical terms apart from academic ones.

2010年2月16日 星期二

¡El Carnaval de Oruro! / The Carnival of Oruro!

Ya, basta con este ¨corriente de conciencia¨ estilo de escribir. Sólo me llevo a escribir demasiado y me causa a agotarme traduciendo mis largos párrafos. Ahora misma hablemos de lo importante: los detalles del Carnaval.

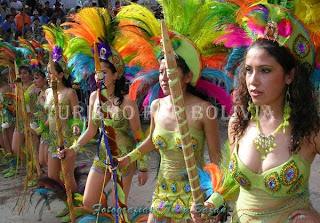

Como dije antes, el Carnaval consiste en danzas de grupos de todo el país: danzas campesinas, danzas indígenas, danzas urbanas, etcétera. En realidad, estas ¨danzas¨ eran más como un largo desfile, porque sencillamente no se puede bailar algo complicado continuamente por tres horas, el tiempo que se necesitaba para los bailadores a cruzar todas las calles que eran involucrados en el Carnaval. Además, sólo las bailas de los hombres pudieron ser llamado ¨danzas¨; la mayor parte de mujeres sólo era responsable por llevar hermosas ropas con cortas faldas. La ¨danzas¨ que ellas presentaban consistían en agitar sus faldas y mostrar sus lindas piernas – aunque no todas eran lindas... también había mujeres mayores que llevaban las mismas cortas faldas, ¡que desastre! A principios de estas actualizaciones, me complacía mucho la bellavista que proveían estas piernas, pero luego me volví harto de la constante repetición de estas danzas. Ya no importaba si sus piernas eran bonitas – ¡hagan algo diferente con ellas nomás!

Hablando de hermosas ropas, debo decir que la principal atracción del Carnaval era las prendas que llevaban los bailadores, porque aun las danzas de los hombres se tornaron aburridas luego. Había trajes de todo los que puedes imaginarte, desde lindos conjuntos de osos hasta espeluznantes de diablos. Algunos se vestían como robots, acompañando a las mujeres en sus típicos vestidos de cortas faldas. También había prendas que tenían luces pequeños por la noche, mientras otras emitían fuego de las bocas de monstruos. Pese a la diversidad de estas prendas, debo decir que perdí mi interés en el desfile después de un poco tiempo, porque sencillamente no soy el tipo que la gusta pasar demasiado tiempo por una celebración. Ciertamente disfrutaba de tirar globos contra personas que empezaron disparándolos a mí, pero luego me aburrían las danzas y me molestaban muchísimo los borrachos. Ellos orinaban en las calles, lanzaban corrientes de cerveza por todas partes, y en general sencillamente epitomizaban los más estúpidos aspectos de humanidad.

De todos modos, hablando de globos, lamento decir que mi mala puntería había causado unas causalidades desafortunadas: una vez les mojé a unos policías cuando mi globo se rompió en el aire antes de llegar a su objetivo, y otra vez una pobre abuelita que estaba gozando del desfile recibió mi maravilloso regala en su espalda. Estuve tratando de mojar unos chicos cercanos, pero por accidente le atacó la pobrecita en vez. Bueno, por lo menos no hice daño a la cara de un bebé con un globo tirado con todo la esfuerza, como lo hizo un niño de más o menos diez años.

Nos quedamos en Oruro sin dormir (no había ningún lugar para hacerlo) hasta las 8:30 de la mañana del próximo día antes de salir para La Paz. Eso era más de 24 horas sin dormir…probablemente no sea mucho en comparación a otras experiencias que has tenido, pero ciertamente era cansadísimo para mis amigos y yo. Sólo decidí a quedarme por un tiempo tan largo porque había oído que sería un gran crescendo de música por todas las bandas tocando al mismo tiempo por el amanecer. Pero éste resultó ser una desilusión para mí, tal vez porque había tenido demasiadas expectativas hacia este evento antes. La única recuerda divertida durante mi estancia tarde era cuando un semi-borracho acercó a mi amiga inglesa Clare y seguía tratando de conversar y hasta pretender bailar con ella. A Clare le molestaba él mucho, pero de todos modos era divertido porque él no era agresiva, sólo un poco perdido en su borrachera. Aun bromeé con Clare sobre la ¨hospitalidad boliviana¨ que el borracho estaba brindándole.

De todos modos, me alegro que tuviera la oportunidad de experimentar una de las más famosas celebraciones en Bolivia, pero estoy seguro que no iré allí otra vez. Tomé algunas fotos, gocé de mojar algunos inocentes, y en conclusión, ya he hecho todo lo que necesité hacer en este evento. La próxima vez elegiré un lugar más tranquilo para pasar me tiempo, porque si hay algo que me ha caracterizado desde mi infancia, sería mi amor de la tranquilidad.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

English Version

It makes me proud to announce that my pronunciation of Spanish and repertoire of vocabulary are improving at a rapid pace. Well, to be fair, I'd be a retard if my Spanish isn't improving with the huge amount of time I spend reading newspapers, books, and magazines every day (up to 6 hours if I have the time). Furthermore, I pronounce every word out loud to improve my confidence with the oral aspect of Spanish, especially con the pronunciation of the letters "r" and "rr." For some reason I can't curl my tongue in a form that will correctly pronounce these two letters correctly, and it looks like I'll have to keep working on it for a while into the future before I fully develop the Bolivian accent that I want.

Anyway, today I'm going to write about an event of great importance in Bolivia: the annual Carnival of Oruro, where dance groups from all over the country come together to showcase their respective dances. These dances officially last 18 hours, but many of them continue dancing with enthusiastic audience members for up to two more days before they exhaust themselves and fall asleep. Another indispensible aspect of this Carnival is the presence of water balloons and water guns, accompanied by canisters of foam-spray to be fired at whoever enters your sight. Beer also plays an important role in this occasion of celebration: After all, the Carnival's principal sponsor was a beer company called "Paceña," a word that means someone or something that comes from La Paz.

Together with people from the rest of the country, my friends and I looked forward to the Carnival with high expectations. On the night before the Carnival, we woke up at 4:30 a.m. and left from La Paz to Oruro (a small city where the Carnival takes place) by bus. We had to arrive at the bus terminal in La Paz around 3:30 a.m. so that we could buy our tickets before our huge flock of similar-minded competitors filled up all the spaces on the bus. There were also private minibuses and "trufis" (they're kind of like taxis, except a little bigger) that could have took us to Oruro, but they were much more expensive — well, if you convert the prices into U.S. dollars, everything in Bolivia is going to look cheap, but in comparison to the prices of the big buses that my friends and I managed to board, those minibuses and trufis were relatively expensive, costing over double (some even close to triple) the price. But then again, the money that we saved from taking the big buses didn't come without a price itself: We had to wait in a super long line, in which a lot of people chose to selfishly cut the line instead of playing by the rules. This situation continued for a long time before some security guards finally stopped these guys from continuing to do so. All in all, I think we waited for at least 45 minutes before securing our tickets. A long time indeed, but at least at lot better than the time I had to wait for similar services in India :). In India, just when you think there can't be any more chaos, I assure you that you'll encounter another frustrating surprise.

But why on earth did we have to wake up so early, you might ask? It's just that the Carnival kicks off really early, and we had to arrive in Oruro as early as possible to get seats before they were all sold out. I would have preferred to arrive in Oruro the previous evening and spent the night there in a hostel, but due to Oruro's small size, pretty much all the hostels, hotels, and private residencies were all booked, while those remaining charged astronomical prices. If La Paz and Oruro had been far away from each other, we would have taken an overnight bus and gotten a good night's sleep (relatively speaking), but Oruro was only 3 hours away from La Paz. By the way, 3 hours is super short by Bolivian standards: Most intra-city bus trips take around 10 hours or more. Anyway, add up all the factors, and you'll come to the conclusion that we had to leave at 4 a.m. from La Paz. There wasn't any better alternative.

Anyway, we arrived in Oruro pretty early and managed to secure great seats for pretty good prices. All in all, we spent around 170 "Bolivianos" (Bolivia's official currency, also known as "pesos") per person on this trip, less than half the amount we would've paid if we had gone with the cheapest available travel agency. I really feel proud that I've yet again saved a bunch of money by traveling without a travel agency. In reality, these agencies only continue to exist due to the demands of customers who know nothing about traveling — I dare say that you'll always have a better experience traveling with a guidebook rather than an agency. The freedom of encountering unexpected adventures is something that travel agencies will never be able to offer you :)

Alright, enough of this stream of consciousness style of writing. It's only making me write too much and causing me to exhaust myself when I try to translate my excessively long paragraphs. Let's start talking about the important stuff straight away: the details of the Carnival!

Like I said before, this Carnival consists of dance groups from all over the country: countryside dances, indigenous dances, urban dances, etc. In reality, these dances were more like a huge parade, because it's just simply not possible to continue dancing something complicated for 3 straight hours — the time that it took for these dancers to cross all the streets that hosted the Carnival. Besides, only the dances performed by men could really be called "dances"; the only thing the women dancers were responsible for was to put on dazzling dresses with super short skirts. The "dances" that they presented consisted of shaking their skirts and showcasing their beautiful legs — although not all of them were beautiful… there were also some pretty old women who wore the same miniskirts… dang, what a disaster! In the beginning of these performances, I have to admit that I was pretty absorbed by the pleasing view that these dancers offered, but afterwards I just got tired of seeing the same thing hour after hour. It didn't matter how pretty their legs were anymore — just do something different with them, for god's sake!

Speaking of dazzling dresses, I have to say that the principal attraction of this Carnival was the costumes that the dancers wore, because even the energetic performances of the male dancers became boring after a while. There were costumes of pretty much anything you can imagine, from cute outfits of a funky-looking type of bear to terrifying suits of the devil. Some performers dressed up as robots, accompanying women with their typical dresses with miniskirts. There were also outfits that had little Christmas lights on them at night, while others breathed fire out of the mouths of monstrous creatures. Yet despite this amazing variety of outfits, I've got to say that I lost my interest in the Carnival pretty quickly, simply because I'm not the type who likes to spend too much time in a single celebration. I certainly enjoyed chucking water balloons at those who opened fire against me first, but afterwards the repetitive dances began to bore me, and the countless of drunk people really just pissed me off. They pissed in the streets, sprayed beer everywhere, and in general they just epitomized the most embarrassingly stupid aspects of mankind.

Anyway, speaking of water balloons, I regret to say that my poor marksmanship led to quite a few unfortunate casualties: Once I splashed a bunch of hard-working police officers when my water balloon somehow exploded in midair, and another time a poor old grandma who was contently enjoying the Carnival's parade received a marvelous gift of mine on her back. I was trying to hit a couple of little kids near her, but instead I soaked the poor old lady by accident. Well, at least I didn't smack a little baby in his face with a water balloon thrown with full strength like some little 10-year-old did.

So we stayed in Oruro without sleeping (there wasn't any place to do so) until 8:30 a.m. the next day before leaving for La Paz. That's more than 24 hours without sleeping… it probably isn't much compared to some of the experiences that you've had, but it certainly was extremely tiring for me and my friends. I only decided to stay for such a long time because I'd heard that there would be a grand crescendo of music produced by all Carnival's bands playing together simultaneously at sunrise, but this event turned out to be a big disappointment for me, probably because I had expected too much of it beforehand. The only fun memory during this late stay was when a semi-drunk Bolivian approached my British friend Clare and kept on trying to talk and even dance with her. Clare was pretty bothered by this dude, but it was funny anyway because he wasn't really that aggressive, just a little lost in his drunkenness, that's all. I even joked with Clare about the "Bolivian hospitality" that she was experiencing.

Anyway, I'm happy that I had the chance to experience one of the most famous celebrations in Bolivia, but I'm pretty sure that I'll pass up the opportunity to go to one of these Carnivals again. I took some pictures, enjoyed soaking innocent bystanders, and all in all, I've pretty much done all I needed to do in this event. Next time I'll definitely spend my time in a more relaxing place, because if there's a single characteristic that's marked me since my childhood, it'd be my love for tranquility.

2010年2月12日 星期五

La Carta de Raza en La Política Boliviana / The Race Card in Bolivian Politics

En el Dapartamento de La Paz, por lo general siempre gana el partido de Evo Morales, se llama MAS (Movimiento al Socialismo). Si me preguntaras al momento, te diría que el Movimiento al Populismo sería el mejor nombre, pero de todos modos, parece que el candidato de MAS ganará la próxima elección de gobernador otra vez. Pero hace unos días que ocurrió algo bien interesante: El candidato indígena para el MAS, Félix Patzi, fue arrestado por conducir mientras borracho. Inmediatamente, el Presidente Evo le mandó a Patzi que renunciara su candidatura, y acordó hacerlo Patzi al principio. Sin embargo, más adelante cambió de idea cuando le regaron sus partidarios de las comunidades indígenas. Patzi dijo que ya estaba cumpliendo la sentencia que le dio su comunidad indígena para castigarle, y por eso puede seguir su candidatura sin vergüenza.

Aparentemente, en la Constitución de Bolivia, existe alguna ley que le da mucho valor a la justicia comunitaria. La justicia comunitaria es la forma de castigación para la mayor parte de los indígenas, según sus tradiciones antiguas de sus ancestros. Incluye castigos de trabajo manual como construir 1,000 abodes (ladrillos hechos de tierra, agua, y paja), como está haciendo Patzi. A mi familia de La Paz siempre le gusta bromear sobre las supersticiones dentro de estas justicias comunitarias, y por eso probablemente haya un aspecto espiritual muy importante en estas tradiciones. De todos modos, Patzi justifica la continuación de su candidatura con la cumple de su sentencia comunitaria.

Además, Patzi está tratando de desviar la atención hacia su delito por ilustrar su incidente de borrachera como un ataque exagerado por las personas que quieren atacarle por ser un indígena. En otras palabras, Patzi está escondiéndose detrás de un escudo de raza — una estrategia muy genial, debo admitir, porque el tema de raza puede encender fuertes sentimientos que abruman la lógica, especialmente cuando estamos hablando de gente sin una educación completa. Además de manipular el tema de raza, Patzi también está jugando otra fuerte carta en su mano al mismo tiempo cuando dice que ya ha pedido perdón al Presidente Evo y que Evo ya lo aceptó. Evo tiene un posición como el Dios acá para un gran parte de Bolivianos y en particular para la base del MAS, o en otras palabras, la base de Patsi.

Además, Patzi está tratando de desviar la atención hacia su delito por ilustrar su incidente de borrachera como un ataque exagerado por las personas que quieren atacarle por ser un indígena. En otras palabras, Patzi está escondiéndose detrás de un escudo de raza — una estrategia muy genial, debo admitir, porque el tema de raza puede encender fuertes sentimientos que abruman la lógica, especialmente cuando estamos hablando de gente sin una educación completa. Además de manipular el tema de raza, Patzi también está jugando otra fuerte carta en su mano al mismo tiempo cuando dice que ya ha pedido perdón al Presidente Evo y que Evo ya lo aceptó. Evo tiene un posición como el Dios acá para un gran parte de Bolivianos y en particular para la base del MAS, o en otras palabras, la base de Patsi.

En conclusión, aunque Patzi todavía está enfrente de mucha oposición de gente poderosa de su propio partido (como el vicepresidente Álvaro García Linera) que no aprueba de su comportamiento, parece que Patsi podrá mantener su candidatura por Gobernador del Departamento de La Paz sin demasiadas dificultades. Después de todo, las masas son fáciles para manipular, y Bolivia no es una excepción.

.jpg)